When did it open and where does the name come from?

In the 1920s, Enrique Levi had a wholesale bohemian crystal and porcelain import company in Carrer Rosselló. His brother-in-law, Hugo Vinçon, joined the business in the 1930s. In 1935, they decided to move to a more central location on Barcelona’s Passeig de Gràcia to open a store. Enrique Levi had to emigrate during the war and his brother-in-law took over the business. Thus was born Regalos Hugo Vinçon, which opened in 1941.

What was the original location like and how did it evolve?

Initially, the household goods and gift shop occupied only the left-hand side of the space at Passeig de Gràcia 96, with access through the door closest to what is now Avinguda Diagonal. The closest entrance to La Pedrera was the Sala Vinçon, an art gallery that exhibited mainly paintings: still lifes, landscapes and figurative portraits. At the back of the space, with access from what is now Carrer de Pau Claris, they continued with their wholesale business. At the end of the 1940s, Hugo Vinçon joined forces with Jacinto Amat, who had worked in the company since 1935, and who bought the business from the German in 1957. A few years earlier, his sons Juan and Fernando had joined the store, and inherited the business in 1967 after the death of their father. They were the ones who turned it around and transformed it into the store that for many years was a benchmark for good design. From then on, the wholesale and warehouse space was gradually reduced and used for the store. The 1980s, with the incorporation of the third generation of the Amat family (Sergio, Yolanda and Joan Enric), saw the growth of the business and the greatest transformation of the space. In 1985, they acquired the main floor of the building on Paseo de Gracia, where the fashion designer Asunción Bastida had had her workshop for years, and opened the furniture section. In 1989, the warehouse was moved to another location and the store was extended to calle de Pau Claris, so that it was possible to cross the block through the inside of the store. They later acquired the premises of the jeweller Aureli Bisbe’s workshop on Carrer Provença, and Vinçon gained a third entrance on this street. In the 1990s, some of the sections of the business grew and the Amats, always creative and enterprising, opened in other spaces, but on the same block: Tinc Çon, ˗a play on words from the Catalan expression ‘tinc son’ (I have a dream), a store dedicated to everything related to sleeping, and Kitchen Çon, where cooking projects were carried out.

How were the products selected and presented?

When the Amat brothers inherited Vinçon in 1967, they divided the work: Juan would be in charge of finance and management, and Fernando would be in charge of purchasing, the store and communication. At that time the business was in the red, so they made a crucial decision: if they were not going to sell the product, they would at least choose objects that they would like to have in their homes. The Bohemian glassware and porcelain, and decorative ceramics went to the clearance section and Fernando set out in search of different objects, with a modern and functional feel. On one of his trips to London he discovered Habitat (the store created by Terence Conran), which made a great impact on him, both in terms of the product and the way it was displayed and sold. Upon his return they agreed to implement self-service, a totally revolutionary system at the time. The product was presented organised on shelves and by sections (tableware, lighting, kitchen, etc.), and in this way the potential customer could leisurely stroll around and choose the one that most interested them. Vinçon soon became a place to go for a stroll, where discovering new products and shopping was a different experience.

Obviously, the product selection was very personal. Fernando Amat visited street markets, new companies, small studios of designers, craftsmen and artists, and publishers that were founded in the 1970s. At that time, importing international products was difficult, but he established alliances with some companies based in Spain, such as Rosenthal and WFM. Later on, he started to travel abroad to find new products and also to attend trade fairs. Thus, in the 1970s, products from the Far East arrived to ‘Vin Chong’ and became bestsellers, such as the famous Chinese slippers. Another habit that was established was that of ‘Receiving Tuesdays’: entrepreneurs, designers, artisans, dreamer inventors and the odd enlightened person queued up on that day in the hope that their product would be one of those chosen by Amat.

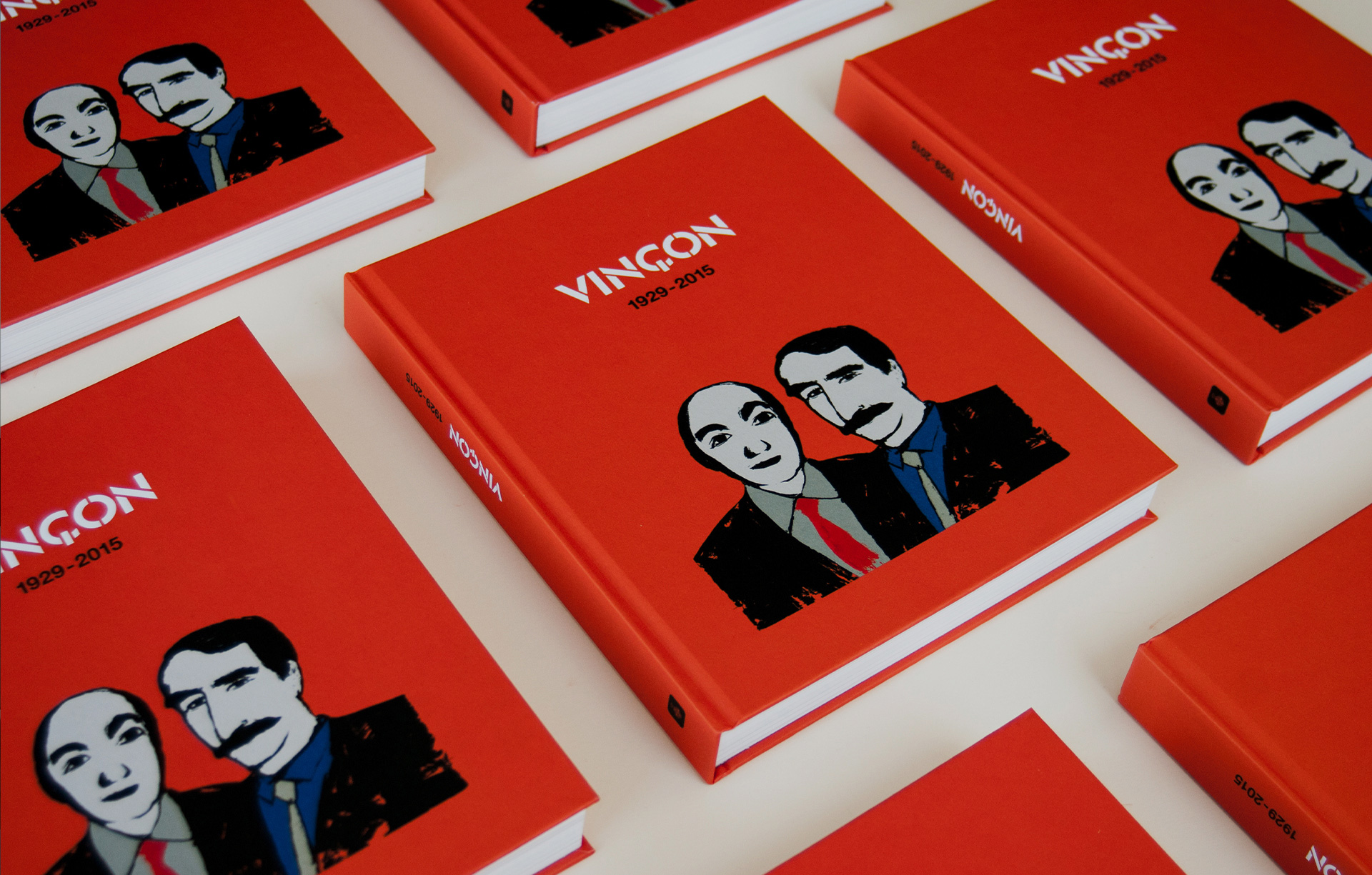

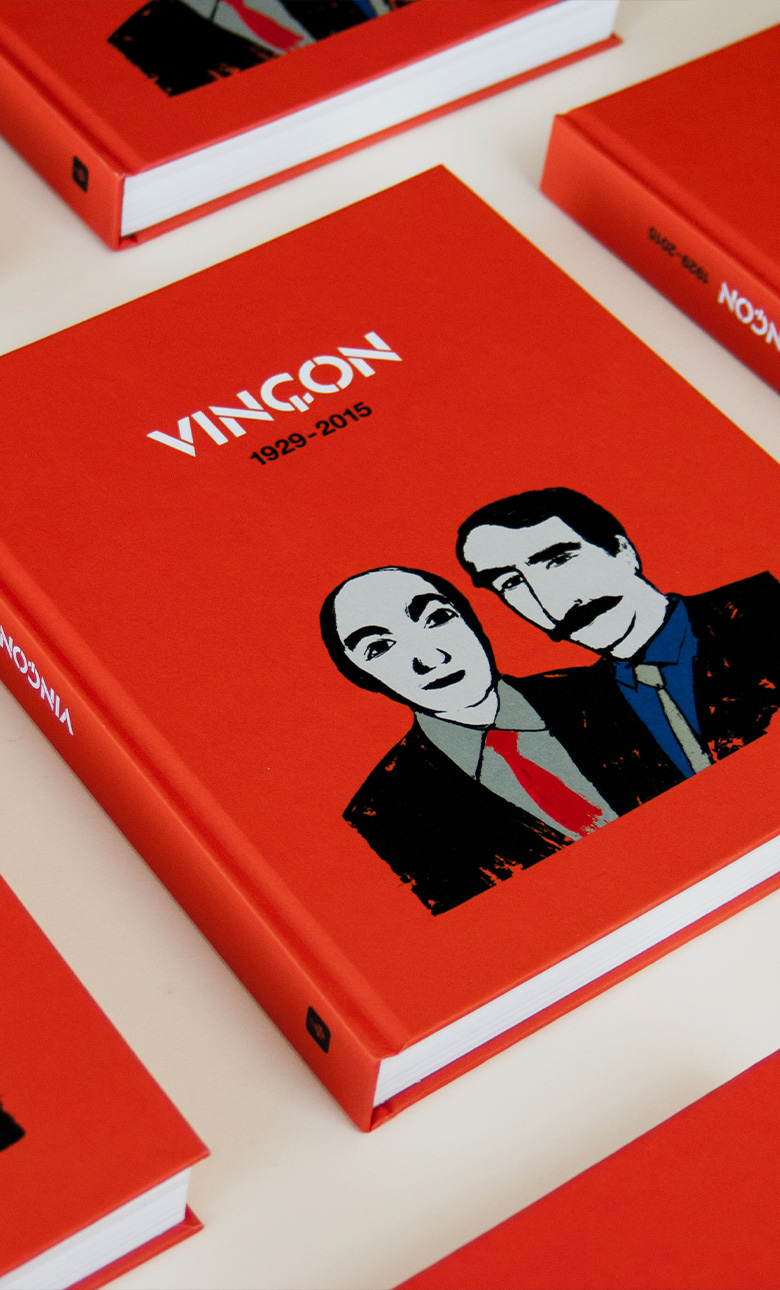

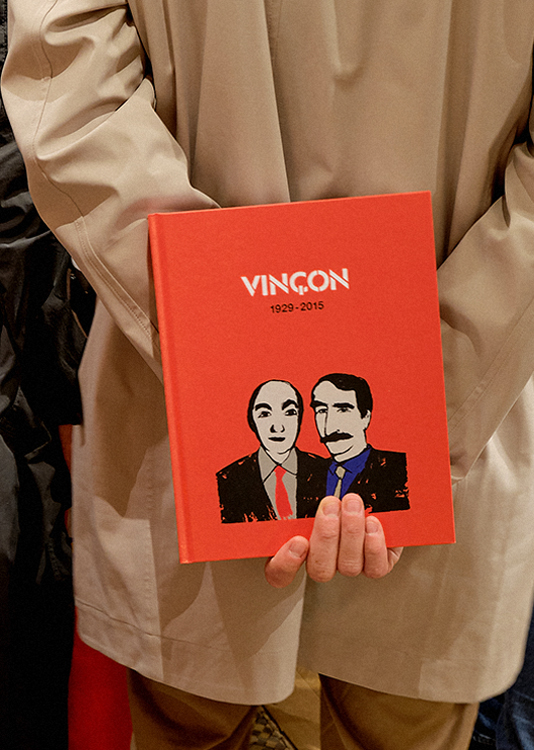

The book, published by Tenov, is the work of historian and designer Oriol Pibernat and María José Balcells, head of historical documentary collections at the Documentation Centre of the Design Museum.

What was the role of La Sala Vinçon?

In 1973, La Sala Vinçon was reopened in what had been the studio of the painter Ramon Casas. If in the previous stage this space aimed to offer a complementary decorative product to the one offered in the store, now the purpose was to broaden the spectrum of customers and present the most innovative art and design. It really was a ground-breaking and successful move. It was a non-profit venue that featured the work of the most alternative artists of the time (the then unknown Bigas Luna, Antoni Muntadas, Fina Miralles and Eugenia Balcells), as well as the work of architects and designers such as Studio Per and Alessandro Mendini. In the 1980s, La Sala Vinçon focused on design, being the first establishment in Spain to feature the work of national and international professionals and companies (Philippe Starck, Ron Arad, Javier Mariscal, Grupo Transatlàntic, Disform and Marieta, among others). La Sala was a gift to the city, while helping to create a community of creators linked to the store and to bring all kinds of audiences together.

Who conceptualised window displays, and how?

The first window displays that featured the ‘Vinçon style’ and won awards were done by Fernando Amat himself. Gradually they were professionalised and Ramon Pujol was the first person responsible for developing them. He was free to put ‘anything’, ‘even if it was from Vinçon’. The idea was not to show products but to create narratives; to catch the eye and steal a smile from the passer-by. They created their own style that played with repetition, irony and surprise, managing to attract attention from afar. Many pedestrians crossed the street to see Vinçon’s latest invention. Antonio Iglesias started as Ramon’s assistant and succeeded him as window dresser for the store’s last twenty years.

Was there a communication strategy?

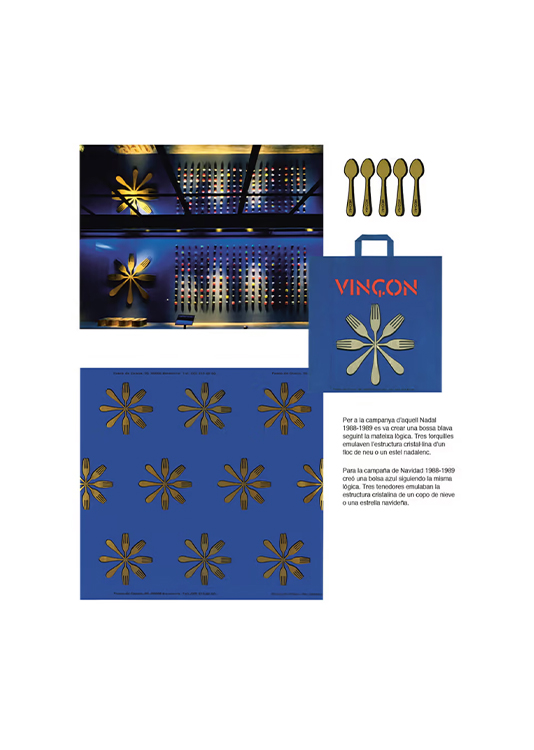

If we had to sum up Vinçon’s communication strategy in two words, they would undoubtedly be irony and surprise. At a time when store communication was practically reduced to window displays and the odd advertisement in the press or a magazine, Vinçon appealed directly to the consumer through action: it invaded the pavements with cows, sheep, geese or mugs, turning them into a party or completely covering its store windows with the slogan: ‘Do you want to see a BIG, BIG window? Come on in…’ Who could resist going on? In this way, the Amats developed their own way of relating to customers, treating them with irony and intelligence. All the store’s messages, from its slogan, ‘extensive assortment of objects of all kinds in general’ to its window displays, wrapping paper and bags were all full of both characteristics. From the beginning of the 1970s, professionals such as America Sanchez, Javier Mariscal and Pati Núñez joined the company, developing powerful ideas while maintaining the store’s freshness and character. The first bag with the green six-fingered hand (Vinçon’s ‘sixth sense’), the one with the slogan ‘Sociedad No Anónima’ with the portrait of the Amat brothers, or the farewell to the peseta were some of the surprising and effective campaigns.

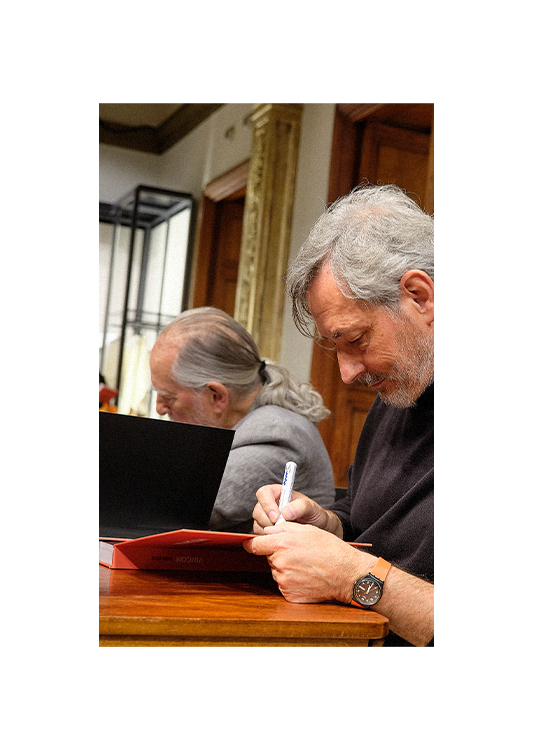

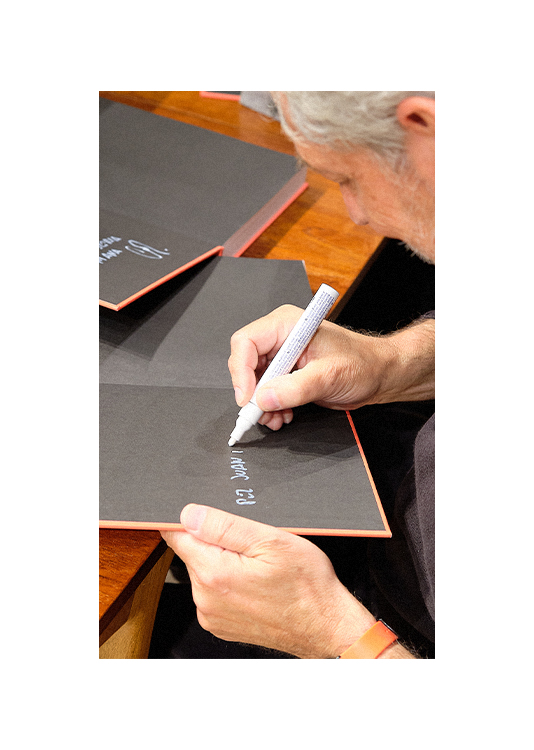

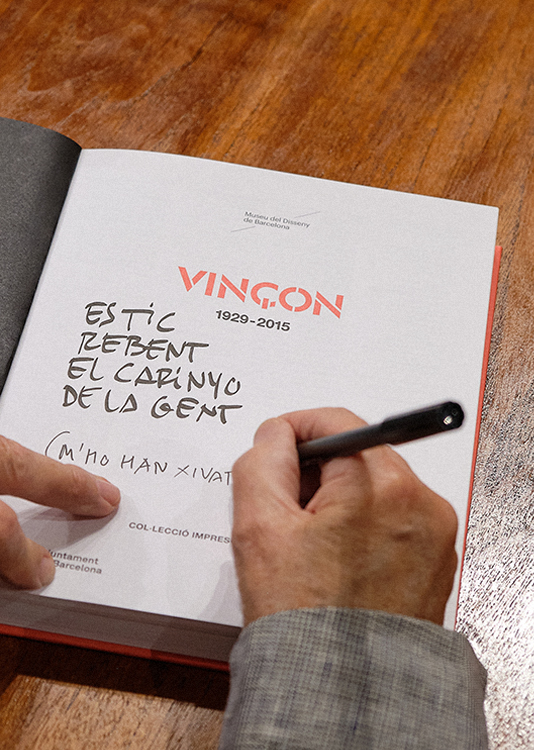

At the presentation event held in the historic building of the Massimo Dutti store at Paseo de Gracia 96, the attendees were able to get their copy signed by the authors.

With this event, Massimo Dutti reinforces its position as a promoter of initiatives that link fashion with the world of art and culture.

How did Vinçon impact the city’s history and become a social and cultural phenomenon?

Vinçon was the first contact with design for many inhabitants at the end of the dictatorship. It is fair to say that he had a powerful influence on the evolution of taste in the social and cultural sectors most open to new concepts. At the same time, Vinçon proposed an appreciation of the aesthetic value of simple, useful, anonymous and commonplace household objects. He also encouraged the value of decorative, unusual and surprising pieces. It was a bazaar that not only offered contemporary design, but, because it was in Vinçon, many objects were understood in their design. A bit like King Midas, but with design. In this sense, it was more than a store and functioned almost like a museum or a school— a place to see and learn, and to come into contact with a completely new culture. Once the design culture in Barcelona and Spain established itself, Vinçon continued to be at the same high level, being a place where you could find surprising quality products, sometimes from big or totally unknown brands. Every visit to the store was a discovery. Moreover, the store became highly identified with the city and its most vibrant sectors. Going to exhibits at La Sala, stopping to admire the window displays, taking a stroll around the store and leaving with a purchase in their unique bags was, for regulars and outsiders alike, a show of Barcelona-ism. For all these reasons, we are not just talking about a store that was successful, but about a phenomenon that altered shopping habits and influenced consumer preferences, and that, in short, radiated modernity from both the Barcelona and Madrid stores.

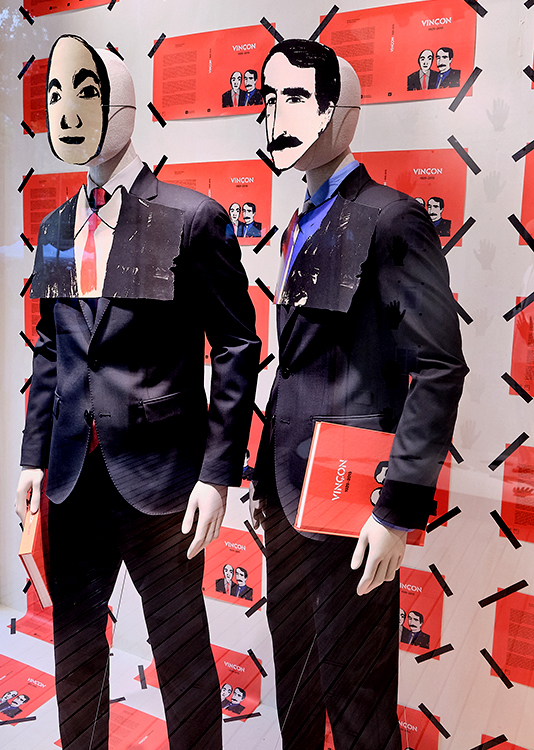

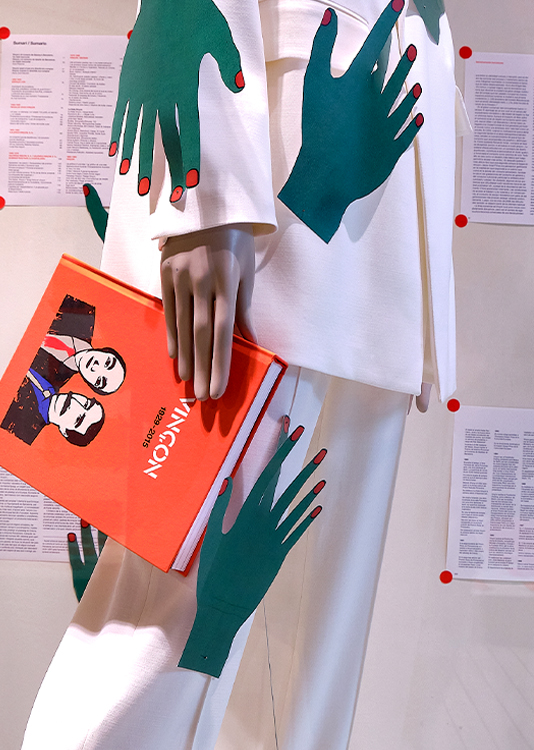

Can you tell us about the tribute window display you did for Sant Jordi’s Day at Massimo Dutti?

Antonio Iglesias (window dressing)

The Sant Jordi window display had to be simple, as it was going to be only for one day, while being very Vinçon. It was about presenting a book, so I decided to focus on the language of the book itself. I used the covers and inside pages of the book, organised as a repetitive grid that created a striking and visually powerful background that echoes the strategies used in Vinçon’s window displays. I decided to include only paper elements as a tribute to the object of the book itself, elements that played with the Massimo Dutti mannequins dressed in their clothes and that were, at the same time, very representative elements of Vinçon. In a window display, the drawn torsos of Juan and Fernando, the owners of Vinçon, were superimposed on the mannequins; this brought a touch of irony to all the layers of the story, as it seemed as if Mariscal’s drawing of the two brothers for a Pati Núñez bag had come from the cover of the book and taken shape. In the other, the six-fingered paper hand created by América Sánchez for the first Vinçon bag poetically caressed two mannequins dressed for spring. In addition to the book, I wanted to include iconic images of the store to also pay homage to some of the designers who were key to the its history.